THE DREAM

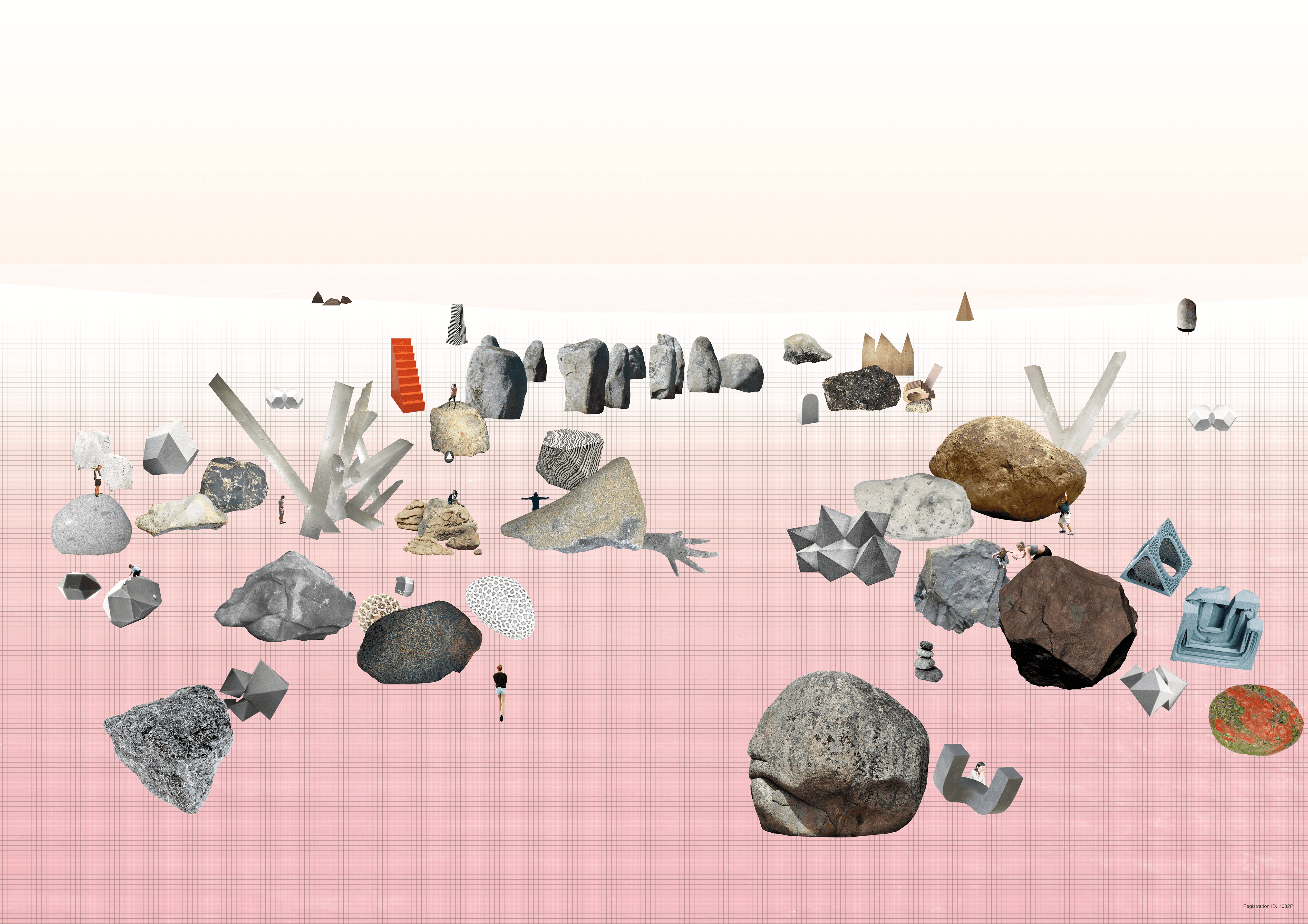

Sifting a landscape of punchlines in search of the set up

Thomas Cole’s 1840 painting The Architect’s Dream is a backward gaze depicting the history of architecture as a perfecting arc pushing teleologically closer to God, “ever hovering on the verge of the impossible.” The mind, he wrote, “takes wing and soars into an imaginary world.” While modernity repeatedly atomized such linear, monolithic meaning, doesn’t architecture remain “hovering on the verge of the impossible?” If so, what does the architect’s dream long for today? What are its monuments, its ghosts?

Yet by its very presence, it says that, in the background, there is something else.

Bernard Tschumi, The Pleasure of Architecture

Bernard Tschumi, The Pleasure of Architecture

In theory and practice, architecture has grappled with modernity ever since the veil lifted that concealed the relativity of time, muting the linearity of history and meaning, the cartesian authority of space, and the morality of classical virtue. Simultaneously, the contexts of architecture have radically morphed with globalization, the digital milieu, and countless other forces that amplify these upheavals. And yet architects today experiment with rich breadth and curiosity, jumping like quarks between the avant garde, PoMo, digital despair, wit, platonic blasé, and Corbusier’s briar pipe. Coupled with a pervasive backlash in culture against the inauthenticity of modernity, architecture now obsesses about things—ontic instances of objects—and encounters them as fragments necessarily imbued with an underlying, phenomenological power. There is, to recast Tschumi, “something more.” We wander among modernity’s ruin, searching for meaning, encountering fragments as possible architectures, and finding in them a self-actualizing force—a cosmos unto itself which poses its own questions and supplies its own answers, ambivalent to the past century’s endless ruminations of architecture’s contingency.

In this context architecture is a mediating, appropriating force, which presents primitive objects and things dispassionately, as both the set-up and the punchline. The Dream explores this terrain and concludes that today there is no paradox in architecture—it yearns “to be defined by the questions it raises,” but takes authorship over neither. Meaning is in the closeness of things in the world not by measure of distance but by a thing’s presence, its sway. We find ourselves in a dream, searching a landscape of primitives in the afterglow of modernity; we are groundless but searching for the elemental, carrying the spirit of the Avant-garde but with nothing to resist, asking questions as though seeing for the first time. Learning again.

In this context architecture is a mediating, appropriating force, which presents primitive objects and things dispassionately, as both the set-up and the punchline. The Dream explores this terrain and concludes that today there is no paradox in architecture—it yearns “to be defined by the questions it raises,” but takes authorship over neither. Meaning is in the closeness of things in the world not by measure of distance but by a thing’s presence, its sway. We find ourselves in a dream, searching a landscape of primitives in the afterglow of modernity; we are groundless but searching for the elemental, carrying the spirit of the Avant-garde but with nothing to resist, asking questions as though seeing for the first time. Learning again.

Caught, then, between sensuality and a search for rigor, between a perverse taste for seduction and a quest for the absolute, architecture seemed to be defined by the questions it raised.

Tschumi, Architecture and Transgression

Tschumi, Architecture and Transgression