DE-SPUR DETROIT

Reconnecting the historic neighborhoods of Detroit to downtown through freeway removal

As the state of Michigan considers spending $1.8 billion to add one lane to less than seven miles of I-94 in urban Detroit, the legacy of race-targeted infrastructure development still simmers. Instead of one new lane, such extensive road investment can help repair and strengthen the city not just to mitigate, but undo, the mistakes of the past

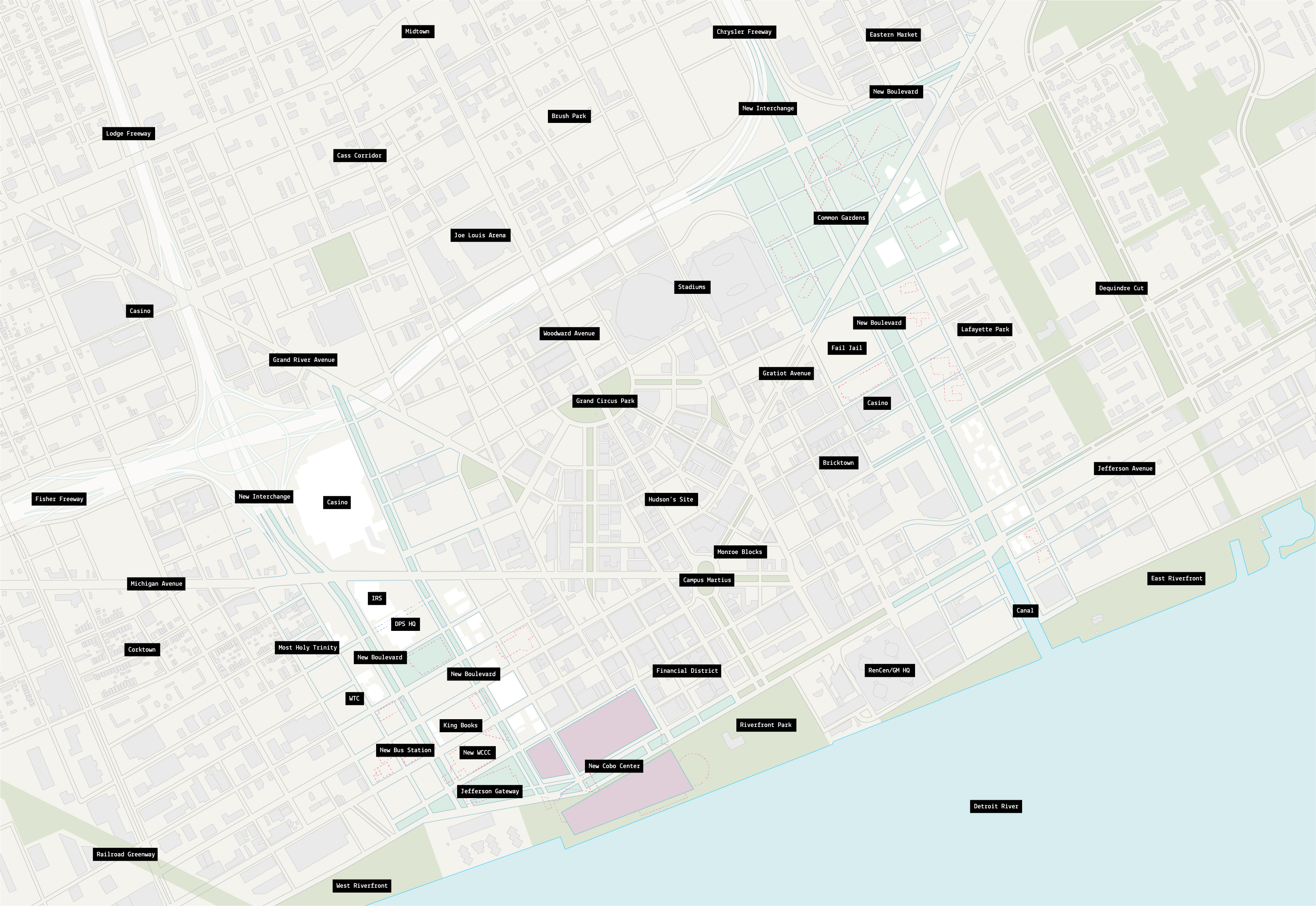

De-Spur Detroit is an ongoing series of studies and proposals for removing two freeway spurs that bracket downtown Detroit: the Lodge and the Chrysler Spur. The project proposes creating a new taxonomy of public spaces that results from the removal of the freeways and its supportive buffers.

Lodge Freeway

After the Davison Freeway gave Detroit—and the nation—a model for the sunken urban freeway, the Lodge was next to be built beginning in the early 1950s. The freeway follows an already-established route out of the inner city to the northwest. But at its terminus in downtown Detroit, it becomes an invasive spur after intersecting with I-75, gently curving through Detroit's oldest neighborhood before disappearing under the immense span of Cobo Center where it ends in obscuration, emerging on the other side as Jefferson Avenue, Detroit's waterfront boulevard. As a spur, the freeway doesn't do much except distribute traffic to the downtown grid through the typical, bloated logic of most urban infrastructure.

De-Spur Detroit proposes to retain the intersection with I-75 and convert the rights of way to a surface boulevard rerouted to fit the existing street grid, eliminating the disruptive curve. The move exposes new city blocks within this grid, reclaiming vast area for development.

Importantly, the proposal allows for the preservation of every historical structure in the corridor, while removing only a handful of large, industrial structures that pose little value. Two exceptions are portions of the existing bus station and the existing Washtenaw Community College building. However, both exhibit the defensive, bleak architecture constructed in Detroit and in cities around the country common in the glum 70s and 80s. The opportunity to rebuild these facilities offers institutional transformation, not merely new buildings.

Finally, the proposal imagines a completely reconstructed Cobo Center that retains and expands floor space (in part by taking advantage of the freeway's excavated right-of-way) while allowing an extension of the Jefferson Avenue boulevard to cut through the site, leading to a new gateway to downtown where it intersects with the boulevard that leads traffic to the Lodge and, as it has for decades, to points northwest.

![]()

De-Spur Detroit proposes to retain the intersection with I-75 and convert the rights of way to a surface boulevard rerouted to fit the existing street grid, eliminating the disruptive curve. The move exposes new city blocks within this grid, reclaiming vast area for development.

Importantly, the proposal allows for the preservation of every historical structure in the corridor, while removing only a handful of large, industrial structures that pose little value. Two exceptions are portions of the existing bus station and the existing Washtenaw Community College building. However, both exhibit the defensive, bleak architecture constructed in Detroit and in cities around the country common in the glum 70s and 80s. The opportunity to rebuild these facilities offers institutional transformation, not merely new buildings.

Finally, the proposal imagines a completely reconstructed Cobo Center that retains and expands floor space (in part by taking advantage of the freeway's excavated right-of-way) while allowing an extension of the Jefferson Avenue boulevard to cut through the site, leading to a new gateway to downtown where it intersects with the boulevard that leads traffic to the Lodge and, as it has for decades, to points northwest.

Chrysler Freeway

![]()

![]()

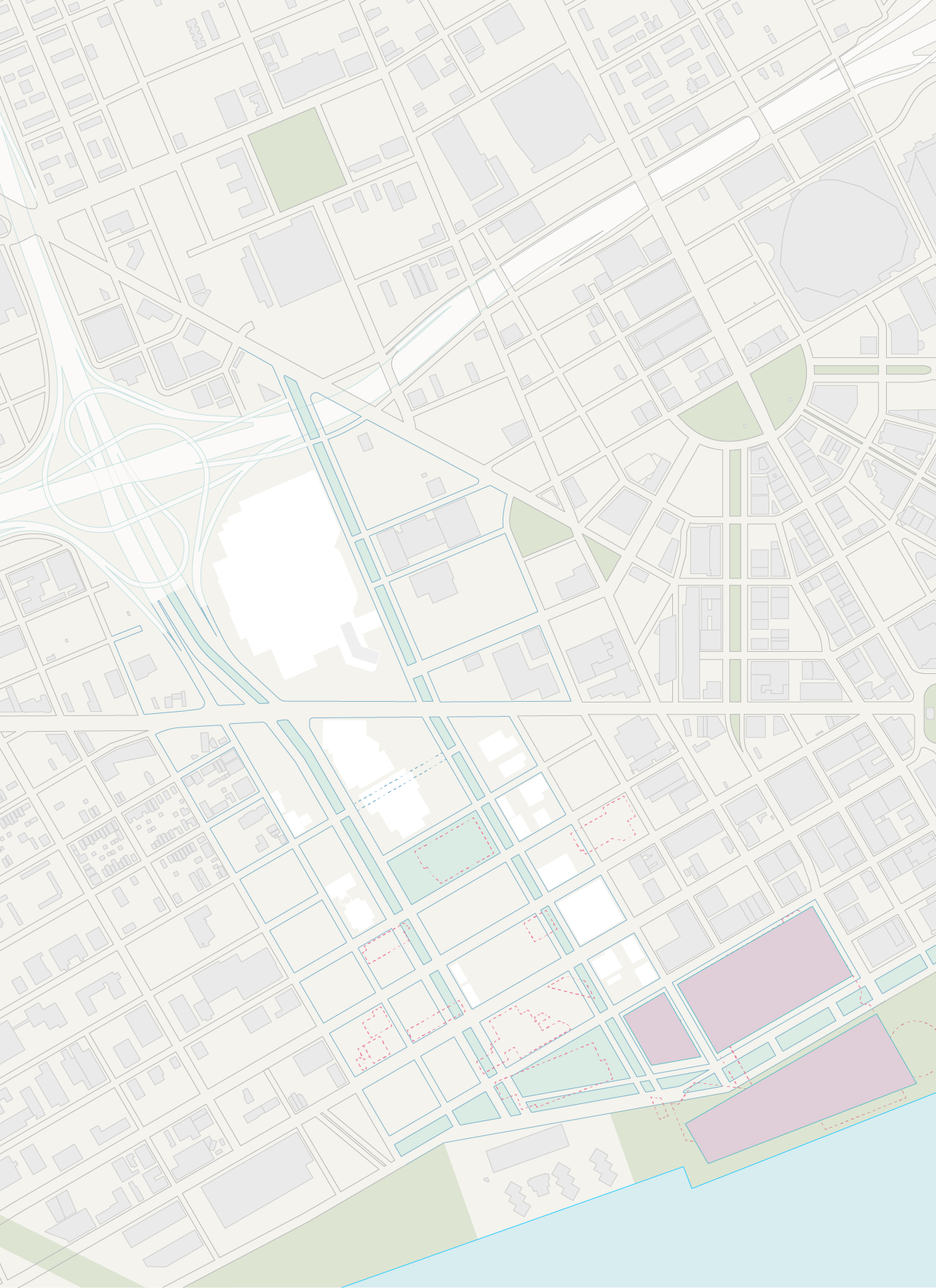

When planners charted the course of the downtown spur of the Chrysler Freeway (I-375) in the late 1950s, they took care to oblierate the heart of Black Bottom, a historic center of Detroit’s African-American community historically anchored along the Hasting Street corridor, the underlying axis of the Chrysler Spur’s right of way. In 2013, the Michigan Department of Transportation announced that it was studying a permanent removal of the spur in order to replace it with a boulevard. Planners have long cited the spur as an ideal candidate for freeway removal, and the move has won community support.

De-Spur Detroit takes this initiative a bit further, and proposes to reclaim a larger swatch of the city by swapping out large, disconnected strutures for a new civic commons and open greenway. The resulting “park” responds to potential new forms of public space that have emerged in Detroit over the last several decades—for example, the presencing of native landscapes, the status of ruins as tourist site, large-scale urban agriculture and even urban forestry, and the inversion of rural and urban typologies.

The new park reconnects four neighborhoods currently cut off by freeways—Brush Park, Downtown, Lafayette Park, and the Eastern Market. The new park is a microcosm of the Jeffersonian grid that rules the southern Michigan landscape, and similarly offers unbroken blocks of programming and use. Orchards with regional fruit trees, open marsh and cattail beds, native oak scrub prairie, and large community gardens make up the blocks. In this way, the park is envisioned as the heart of the city (not merely downtown) and a type of commons not historically seen in the Midwest. The realigned boulevard passes through the new civic commons and remains an arterial route into and out of the center city, and ties into the reconnected street grid of Black Bottom.

De-Spur Detroit takes this initiative a bit further, and proposes to reclaim a larger swatch of the city by swapping out large, disconnected strutures for a new civic commons and open greenway. The resulting “park” responds to potential new forms of public space that have emerged in Detroit over the last several decades—for example, the presencing of native landscapes, the status of ruins as tourist site, large-scale urban agriculture and even urban forestry, and the inversion of rural and urban typologies.

The new park reconnects four neighborhoods currently cut off by freeways—Brush Park, Downtown, Lafayette Park, and the Eastern Market. The new park is a microcosm of the Jeffersonian grid that rules the southern Michigan landscape, and similarly offers unbroken blocks of programming and use. Orchards with regional fruit trees, open marsh and cattail beds, native oak scrub prairie, and large community gardens make up the blocks. In this way, the park is envisioned as the heart of the city (not merely downtown) and a type of commons not historically seen in the Midwest. The realigned boulevard passes through the new civic commons and remains an arterial route into and out of the center city, and ties into the reconnected street grid of Black Bottom.